~This is the first of four guest posts from a class taught by Tom Ewing at Virginia Tech in fall 2017. Read the other posts here: II and III.

The Spanish Influenza of 1918 demonstrates the unique scholarly value of the state medical journal collection from the Medical Heritage Library (link). The Spanish flu affected the entire United States (as well as the world) in ways that challenged the current state of medical knowledge, required mobilization of all available resources, and shaped future understanding of epidemic influenza. State medical journals were part of this history, as they disseminated expert knowledge, reported on cases, and evaluated the impact of the disease on communities and the medical profession at the local and state level.

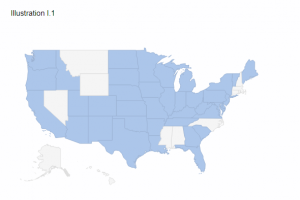

The state medical journal collection in Medical Heritage Library includes journals from 34 states for the years 1918-1919 (See Table I.1.) The available states are marked in the map below (Illustration I.1); in the online version, available here, each state is linked to the journal’s page in Medical Heritage Library and the Internet Archive. In most cases, these two years were published as two separate volumes; in some cases, years were combined or the volumes covered part of a year. Most journals include a table of contents for each volume, which allows searching by author, topic, or article title. The full text search feature in Medical Heritage Library allows for broader searches for keywords. A search for the word, “influenza” in the state medical journal collection for the years 1918-1919 produces 35 results from 21 titles. This search across all titles is less complete than searching individual titles; the Virginia Medical Monthly, for example, does not yield results in the search across the collection even though this keyword appears more than one hundred times in the combined 1918-1919 volume. The “search inside” function of the Internet archive makes it possible to search within a specific volume of each medical journal, as shown in the example for the Journal of the Iowa State Medical Society (Illustration I.2). Because this search is for keywords, however, it highlights every instance of the word appearing, which then requires a review of each page to determine relevance.

State medical journals provide insights into key questions about the 1918 Spanish influenza epidemic related to the severity of the epidemic, the extent of cases and deaths, and the potential effectiveness of preventive measures. The journals are especially valuable for addressing this question because they wrote from a position of authority, their audience included physicians as well as public health officials, and the monthly format allowed for some distance to evaluate the effectiveness of specific measures. The editorials that most journals published each month are an especially useful source for understanding how professionals understood the epidemic and what measures, if any, they recommended to deal with this threat to public health. These editorials can be located using the full text search for each journal or by reviewing each month during the epidemic, as the editorials usually appear in the same location of each issue of the journal. A review of editorials from a small sample of journals suggests important common themes as well as distinctive perspectives on the disease.

In October 1918, the Texas State Journal of Medicine published an editorial that began with the statement, “Influenza is now epidemic in every State east of the Mississippi and in many Western and Pacific Coast States. At this writing, seventy-seven counties in Texas have reported influenza as epidemic.”(1) After reviewing the number of cases reported across Texas, the editorial offered this sweeping criticism of public health readiness to deal with the epidemic: “The present crisis emphasizes the utterly unprepared condition of our communities. We have no surplus hospital facilities, even in our municipal institutions, and our health department is so poorly financed as to have no material assistance to offer. Added to this is our present shortage of doctors and nurses.” The editorial reviewed current understanding of disease transmission and then concluded with a lengthy quotation form the Journal of the American Medical Association based on a physician’s first-hand study of cases at a Massachusetts military base.

The Journal of the South Carolina Medical Association also published an editorial, signed by J. Heyard Gibbs, in its October 1918 issue, which also began with a statement of the scope and severity of the epidemic: “At present time the physicians of South Carolina, in common with members of the profession generally throughout the country, are having their mental and physical energies taxed to the utmost through the unprecedented demands made upon them by the prevailing epidemic of influenza.” (2) The demands of military service had deprived many communities of doctors and nurses, but the editorial praised those who serve the population of South Carolina: “The physicians generally have responded in heroic fashion to the increased demands made upon them, and lay women have exhibited a commendable spirit in their desire to aid in the nursing of these patients.” After an extensive review of symptoms, the editorial provided an outline of recommended treatments for individual patients, including rest in bed, simple diet, and measures directed to relief of symptoms. The editorial concluded with a prediction of a lengthy period of epidemic disease — although with no mention of the likely scale of deaths: “Each of our communities may look forward to approximately six weeks of an active epidemic, the disease usually requiring from two to three weeks to reach its height and a corresponding length of time for the decline. But at the end of this time we shall not be through with our difficulties. We shall probably have epidemic influenza throughout the winter months, and we cannot give too much attention to our preparation for handling this disease.”

An editorial, also with the simple title, “Influenza,” in the Illinois Medical Journal in December 1918, began with a frank admission of the limited understanding of the disease even after two months of epidemic conditions: “The fact that a well informed medical man will make a clear positive statement regarding the disease and immediately another well informed medical man disputes the truth of such a statement and takes an exactly opposite view, indicates that really there is little known about it.” (3) After reviewing conflicting opinions from doctors and other experts about the value of quarantine, masks, and vaccines, the editorial came to the same conclusion as other journals about the limits of knowledge even after several months of dealing with the epidemic: “The reading of the influenza literature which has appeared until now, thoroughly convinces one that comparatively little is known about it. Many statements now widely published will be subjects of ridicule shortly….The wearing of face masks in hospitals when done intelligently is probably advantageous, but really the recommendation of a face mask for a pedestrian or charwoman is about equal in intelligence to that of advising a manipulation of the spine.”

In November 1918, the California State Journal of Medicine published an editorial stating that “Epidemic influenza has reached the Pacific Coast in its pandemic progress from Eastern Europe around the world.” (4) After reviewing the history of epidemic influenza as well as the death rates from related diseases, especially pneumonia, in past and current epidemics, the editorial cautiously predicted that “there is reason for believing that this mortality will be lower in California.” After reviewing specific symptoms of the current disease, the editorial connected the limited knowledge about the disease to the need for a cautious approach among medical professionals: “No specific treatment for influenza is available but because of the near-hysteria attending the popular interest in this epidemic, numerous sure-cures are receiving publicity in both medical and lay circles. Physicians should be conservative, yet open-minded, on this subject.” The editorial offered a detailed description of the “most successful symptomatic treatment,” which included salicylic acid, high fluid intake, rest, good diet, and attention to complications. Asserting that “prophylaxis is of utmost importance,” the editorial offered this confident statement: “Absolute quarantine will prevent introduction of influenza,” including hanging sheets between hospital beds, making doctors, nurses, and attendants wear masks at all times, careful washing of hands, use of disposable tissues in place of handkerchiefs, and finally a series of steps easily implemented by the public: “Prophylaxis should include sufficient sleep, rest, open air, and sunshine. Crowded street cars and indoor gatherings of all sorts must be eschewed. Sneezing or coughing without the face protected by a handkerchief is a sanitary crime. Spitting should be similarly repressed. Gauze masks should be worn in public by all persons where influenza is epidemic.”

An editorial in the November 1918 issue of Northwest Medicine, serving the states of Oregon, Washington, Idaho, and Utah, reported that the cities of the Northwest had also experienced “the full effect of the influenza epidemic which progressed with great speed from the Atlantic coast.” (5) The impact of the “influenza scourge” has been felt most severely in army camps, but also in among civilian populations, with “the most appalling feature” being the high death rates from pneumonia, leading to this evaluative comment: From a medical standpoint te most appalling feature of the epidemic has been the fatalities from a form of pneumonia with which the average practitioner was totally unfamiliar. In spite of all efforts to check its advances, in many cases the medical attendant has been practically helpless in face of the rapid and unopposed progress to a fatality.” The fact that “the epidemic appears to have created less havoc in the cities of this section” led the journal to praise the prophylactic measures, such as closing schools, churches, theatres, and other places of assembly, implemented by public health officials and generally accepted by the population: “The few individual objectors to wearing of gauze masks and other sanitary provisions have been negligible in comparison with the unanimous compliance with the stringent requirements to check the spread of the disease.” The editorial concluded that these measures had been generally successful in the Northwest states, even as it looked forward to the end of the epidemic: “The fact that the epidemic appears to have created less havoc in the cities of this section than in some others in the country would lead one to place some confidence in the effectiveness of these various measures of prophylaxis which were enforced with considerable degree of severity. At this time it appears that the epidemic is wearing itself out and it is hoped that it will soon be a thing of the past.”

An examination of these five editorials across journals provides some sense of how medical professionals made sense of an unprecedented challenge to public health. The influenza in 1918 seemed familiar, yet the mortality associated with this epidemic, particularly from pneumonia, puzzled physicians and medical researchers. The prophylactic measures were generally endorsed by the medical journals even as they acknowledged the limits of such measures. These editorials suggest that the editorial staff of medical journals, like the profession more generally and indeed the nation as a whole, looked ahead to the end of the epidemic even as they admitted that the disease was poorly understood and thus difficult to control in the present or prevent in the future.

Footnotes

- Editorial, Texas State Journal of Medicine, Vol. 14, No. 6 (October 1918) pp. 217-218 (link).

- “Influenza,” Editorial, The Journal of the South Carolina Medical Association, Vol. 14, No. 10 (October 1918) pp. 247-248 (link).

- “Influenza,” Editorial, Illinois Medical Journal, Vol. 34, No. 6, December 1918, pp. 337-338 (link).

- “Influenza,” Editorial, California State Journal of Medicine, Vol. 16, No. 11 (November 1918), pp. 479-481 (link)

- “The Influenza Scourge,” Northwest Medicine, Vol. 17, No. 11, November 1918, p. 320 (link).

Pingback: Guest Posts: II. Case studies from Student Research Projects in Data in Social Context Class – Medical Heritage Library